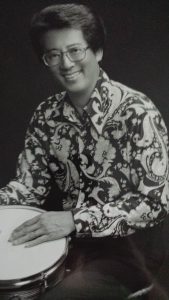

Hawaii’s Living Legend, ‘Mr. Percussion’

“Before we started rehearsal, for eight-10 months, we memorized everything and played it…played with feeling. We became very popular for that.”

When you talk to Harold Chang, 92, about his moment of fame with Martin Denny (Quiet Village) and the Arthur Lyman Group (“Yellow Bird,” Taboo) — kings of Polynesian exotica — the Hilo drummer always goes behind the scenes, back to the basics: Learn the songs inside-out. Practice, practice, practice. Work hard. Stay open, stay humble.

Chang’s insatiable curiosity, big band obsession, ability to roll with the punches — musically or otherwise (he’d often sneak into USO shows as a young boy during curfew in the middle of WWII!) — and that innate humility would serve him well in the years to come.

Not to mention set him up for legendary status…a status that encompasses milestones many in the industry would envy: longest-living, oldest member of Local 677, circa May 1948, 2017 recipient of Na Hoku Hanohano’s Lifetime Achievement Award, beloved clinician at iconic, now-defunct Harry’s Music Store in Kaimuki.

The drumming veteran also enjoys quite an illustrious past, having rubbed shoulders with quite an illustrious roster of famous musicians and performers in their day, including Don Ho, Hilo Hattie, Jimmy Borges, Steve Allen, Red Skelton, Andy Williams, Dave Weckl, Peter Erskine, Richard Chamberlain, Connie Stevens, and that one time he played with the Nelson Riddle Orchestra for Frank Sinatra.

Don’t forget, Hawaii’s living legend achieved quite a bit of fame on his own later on, with the Ebb Tides, Chang Dynasty, and as co-founder of Makaha Records, with Tom Moffatt, Marlene Sai, Toki Anzai, George J.D. Chun, and attorney David Mui.

Chang enjoyed the prestigious endorsements of Zildjian, Paiste Cymbals, Pearl Drums, and most recently, even into his 90s, Canopus Drums, which he played at the Na Hokus.

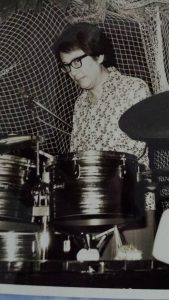

Inspired early on by Gene Krupa’s (“Sing! Sing! Sing!”) unforgettable, big screen, big band drum solos, the local boy from Hilo would absorb everything he saw and heard, alchemized and translated into his own extraordinary, ambidextrous, rolling, floating style, in the most unlikeliest of venues (La Hula Rhumba, Tin Pan Alley’s Beretania Burlesque Follies, Club Hubba Hubba on Hotel Street, assorted Japanese dance shows, Waikiki’s South Seas).

How are you doing with the coronavirus scare?

They’re shutting down everything in town, restaurants, yeah, etc. etc. etc. They’re shutting down every island the same way. In California, they shut down, what, 40 million people now.

In San Francisco, they’re sheltering in place. It’s not as bad in Hawaii, right?

No, but they still, they closed everything down, no events, no entertainment, no sporting events, no nothing. The parks are closed, the zoo’s closed. They’re telling everybody to stay home. It’s good because the more you go out, you become more of a candidate to catch it. It’s very serious.

You know what, you and I are in that category—

Yeah, I am [laughs].

You gotta be careful. You’re feeling okay?

I’m feeling fine.

A lot of people may not know but you were in the Arthur Lyman Group.

Arthur Lyman and also Martin Denny.

Right! “Yellow Bird” was everyone’s favorite song growing up in the ’60s.

That was one thing that we had that was on the national charts for four weeks. The record company gave each of us a single 45 gold record. But, that’s an interesting story. We played to a lot of Jewish people in Chicago. They loved our music. So, we recorded “Hava Nagila.” And the guy at the record company said, “Put that on the single.” Arthur did, and thought it’d sell. Then, he put “Yellow Bird” on the B side, and believe it or not, that’s the one that became #1.

In the post-WWII ’50s-’60s, Martin Denny and the Arthur Lyman Group (pictured) popularized Polynesian exotica — a precursor to world music — worldwide.

How did it feel to be a part of legendary artists, pop culture?

It felt good. A lot of hard work, a lot of traveling, a lot of requests, man, a lot of playing of “Yellow Bird [laughs].” I must’ve done it 5,000 times or more.

OMG.

I’m a percussionist, you know, but for that one, I played bass. We played different instruments for different feelings for our show. We never spoke or sang our shows, we just got ready and we rehearsed. Before we started rehearsal, for eight-10 months, we memorized everything and played it…played with feeling. We became very popular for that.

Want to know something?

What?

Myself and Arthur, we had two changes in our 18-year career: the bass player we changed once, the piano player we changed twice. In my 18 years, I was never sick one time, because no one can take our place. We had to memorize 400-500 songs in our head, the arrangements, everything.

If I ever got sick a little bit, my doctor would come down and give me a shot, down at where we played.

That’s amazing, though, ‘cause nowadays, people get sick left and right, and they have to take a break. But you couldn’t afford to get somebody to sub, because you guys had it all in your head, right?

Absolutely.

I don’t know how you’d be able to teach a sub all the entire repertoire in such a short time!

Cannot. The new bass and piano guys, we’d tell them to listen to our albums, in order to learn. We had 35 albums.

They’d have to learn all those tunes?

At least 100-150.

Holy —! Okay, let’s get to the union. You’re the oldest, longest living Local 677 member in Hawaii. What does the union mean to you and why is it so important for musicians to support, and have, that representation?

I traveled around the world, United States, every place, San Diego, Las Vegas. The musicians union at that time would come and make sure that you are union members, they took care of our contracts, made sure our contracts were honored. I like the union, because at the time, you joined a medical group like HMSA; it’s cheaper to get medical through the union than as an individual. They take care of you, wherever you are. If someone’s not paid, the lawyers take over and get your money for you.

I don’t know why kids nowadays don’t go that route.

What would you say them as a proud, lifetime union guy?

I would say to join the union, make every gig you have— have the buyer sign a union contract. That way, if anything goes wrong, the union would go and fight for you. A lot of times, musicians today they get screwed, non-payment, the pay, you know, below the union scale. Union scale is low as it is now, but musicians working— I couldn’t believe they’re working for the percentage of the bar, the percentage of the cover, and that’s it. How can they make a living? Maybe if they have a day job, probably I’m assuming. A lot of my musician friends have two, three jobs they work all week. Me, I’ve always been a union man my whole life.

When did you join the union?

I was 20. I’ve been a union member ever since.

How did you get your start as a percussionist?

I started at 5, 6, 7 years old. I came to the Big Island, that’s where I’m from, I was raised there, but I was born on Maui. They would send beginner teachers to the outer islands, and my father’s cousin, she’s a music teacher, she would come on the weekends and stay with us and then go back to teach again on Monday. I would beat around on my mother’s pots and pans with chopsticks when I was five-, six-years-old. The teacher gave me my first pair of drumsticks, she taught me how to hold it, how to roll, and it started there. I started beating with regular drumsticks. Then, I took beginning band in intermediate school when I was 12, learning percussion and how to read.

The people that helped me along the way — because during WWII, there were a lot of service bands on the Big Island…we would have maybe three or four days of school, and the service bands would be staying in the school or in the different places, and they’d rehearse, always free all day. So I would go everyday, sit behind the drummer, watching him play, and ask him questions. That was before I started intermediate school, 7th grade.

Then, at night, I would stupidly go see the USO, Army bands perform. Curfew was 9 or something. I would stay up till midnight. If they caught you out after 9, you’d be shot —

Oh no.

…when the cops came out, I would go in the bushes, the trees. They wouldn’t come out, because they were afraid of the Japanese. They’d come out a little more, stand outside the gate, shine a flashlight, then go away. I took so many chances just to watch these bands play at night, they’d do concerts at night for USO people. That was my beginning.

You were headed to Hastings Law School in San Francisco in the ‘50s. But then, something changed.

In 1949, I went to UH paralegal and graduated in 1953. I was playing in a club called Leroy’s on Ala Moana Blvd., but my gig got through at 1 a.m., so late. I had a hard time studying and making my classes. A friend of mine, Bruce Hamada Sr., was working at the Beretania Follies, and his gig got through earlier, at 10:30 p.m. Bruce came into Leroy’s one night, and on a break, we talked about me changing gigs, so I could have more time studying.

I was planning on going to Hastings Law School. At that time, local members of the 100th Infantry and 442nd Battalion were coming back from law school without jobs. They were all working as bartenders and waiters, so I decided not to go to law school. I stuck with music, and eventually, joined Martin Denny’s band, and then, the Arthur Lyman Group in 1958.

How did you find yourself playing with Arthur Lyman?

I was with another group at the time. Princess Kaiulani Hotel Pavilion, it was 12 stories high, it was the tallest hotel in Waikiki. They had the Royal Hawaiian, the Moana, and Princess Kaiulani. We played on the 12th floor of the Mauna Kea Room. Back then, there was also Don, the Beachcomber’s Bar, and that’s where Martin Denny was playing. I’d go down, watch during intermission time. For his first album, Exotica [1957], he asked me to join him, along with Augie Colon. I played as an added percussionist, the hand instruments, the gear, the shakers, etc. etc.

You know there was a movie called, “Breakfast of Champions” in 1999? Martin Denny did the soundtrack. They used his music as the soundtrack throughout the whole movie. They had famous actors in there, Christ!, kooky movie. Martin invited us to go to the Hawaii Theatre to watch the movie. He invited Don Ho, us… Bruce Willis was there, Matthew Broderick, Albert Finney, old time actors… When I first heard the surround sound in the old theater, I had chicken skin. The whole theatre was empty, except for the celebrities.

Arthur Lyman was working as a front desk clerk at the Halekulani for his day job [when Martin Denny heard him play and asked him to join the band]. After two years, Arthur quit Martin Denny’s band. He was working at the Hawaiian Village when Alfred Apaka approached him. Alfred was the entertainment director for Henry Kaiser and he asked Arthur to form a group. Arthur hired John Kramer on bass, Alan Soares on piano, and me on drums.

I was working two gigs every day. Arthur came to see me fortunately, he had the bass player, who also quit, hired me, and we found the piano player. That’s when I joined.

We rehearsed at the Tahitian Room in the Hawaiian Village for one year before we opened. We’d rehearse six-eight hours a day, playing the tunes over and over again, memorizing them. When we opened, everything was perfect. In the coming years, we’d rehearse, memorize it, put it out on the stage, and if anything needed to be fixed, we’d fix it the next week. We did classical songs, Japanese songs, Chinese, Filipino, Hawaiian and on and on. We did conch shells. I think we were the first people to play conch shells. That’s how we started.

How come you were playing exotica at the time, why was it so popular?

Martin Denny made it popular. Nah, he didn’t start it, actually. Arthur, Augie Colon (bongos, congas), and John Kramer, they got treated pretty good. And when they played these tunes, they started throwing a few bird calls in. And Martin, he said, “Eh, that’s good, guys, keep it in!” Martin could never do those, so just the three of them made bird calls, someone would do the bird call from the left of the stage, from the right of the stage, it was very interesting, very catchy. Then, when Arthur started his Group, we did the same thing, because we had experience with it.

I really admire his soulful playing. People would pay to watch him play, even all the biggest artists in the world, Cal Tjader, Red Norvo, Lionel Hampton, because, he had a touch different than all the others. It was amazing to watch him play. Every night, I’d stand behind on the left side of Arthur, and in the front, there’d be 60-75 women just screaming. I could see them looking at his expressions and body movements. The way Arthur could play vibes…it made them go crazy. I asked him one time, “Arthur, how do you do it?” He says, “When I play vibes, I play like I’m making love to a woman.” That’s why they went to his shows. The women felt it.

You still gig, I hear, playing with a 17-piece jazz big band on Mondays.

This band has been rehearsing every Monday for 50 years, unless something happens, like holidays, or someone passing away. All the good musicians that are playing and aren’t working on Monday and want to keep their chops up, they come to the band… We just rehearse big band music every Monday from 7 to 9, different places. We started off at Kamehameha Schools…we went to different schools… Now, we’re at St. Andrew’s Priory band room. Anyone can come.

If you could characterize your playing style…

I think I’m a well-rounded musician. I can play Polynesian, Hawaiian, Japanese, Korean, Samoan, I was brought up in American jazz. I learned how to play pop, rock, and funk.

You’ve left quite a legacy for a lot of musicians. What would you like to be remembered for most?

Eighty years I’ve played drums. I’d like people to remember me as an excellent musician who was on time, never missed a gig, and was always professional.